Старейшее издание Европы и мира – Британская газета "The Times" (город Лондон) опубликовала статью о нашем РАССЛЕДОВАНИИ.

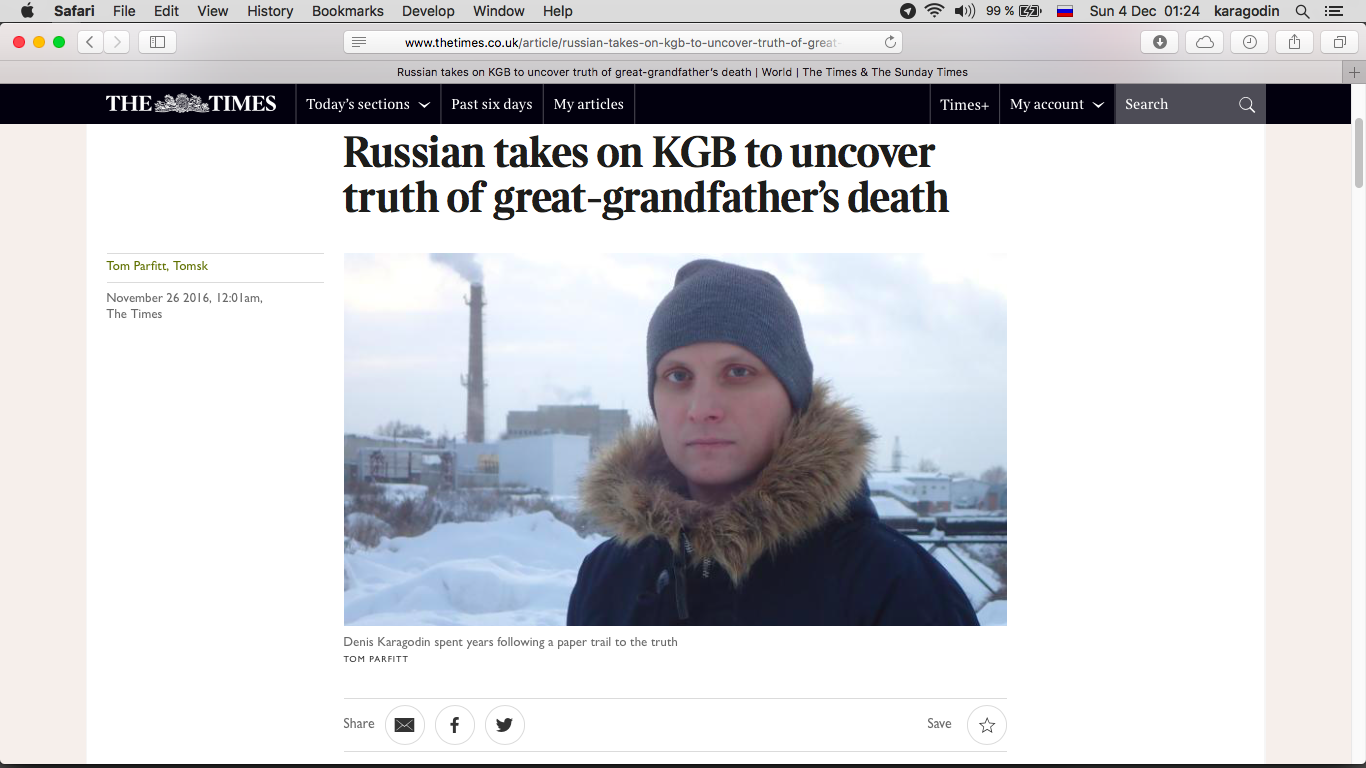

"Russian takes on KGB to uncover truth of great-grandfather’s death" – November 26 2016, 12:01 am, The Times.

Специальный репортаж из Томска (на основе многочасовой беседы с Денисом Карагодиным и городской экспедиции по местам событий) by Tom Parfit:

"Russian takes on KGB to uncover truth of great-grandfather’s death “There’s been a murder.” Those were the words of Denis Karagodin when he marched into the headquarters of the Federal Security Service in the Siberian city of Tomsk, 1,800 miles east of Moscow." – November 26 2016, 12:01 am, The Times – http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/russian-takes-on-kgb-to-uncover-truth-of-great-grandfathers-death-3bzrqfcs2

Благодарим автора Tom Parfit и газету "The Times" за проявленный интерес, профессионализм и объективную подачу информации.

Спасибо!

Russian takes on KGB to uncover truth of great-grandfather’s death

Tom Parfitt, Tomsk

November 26 2016, 12:01am,

The Times

Denis Karagodin spent years following a paper trail to the truth – TOM PARFITT

“There’s been a murder.” Those were the words of Denis Karagodin when he marched into the headquarters of the Federal Security Service in the Siberian city of Tomsk, 1,800 miles east of Moscow.

The duty officer looked startled. Mr Karagodin, 34, was not hotfoot from the scene of a killing, he had come to remind the FSB of the execution of his great-grandfather, Stepan, during Stalin’s purges in 1938 — and to ask who was to blame.

“I decided to treat it like an ordinary crime and to find out the essentials — who was responsible, why, when and where,” he said in an interview.

Four years on and Mr Karagodin, a designer and philosophy graduate, has become famous nationwide with his campaign for the truth.

This month, after thousands of hours of hunting in KGB archives, firing off written requests to truculent officials and fielding messages via his website, he finally identified the three people who shot his great-grandfather.

“I have uncovered the entire chain, from Stalin and the Politburo right down to the very slaughterers themselves,” he said.

Perhaps no individual has ever built up such a detailed picture of how a relative was killed during the Great Terror in the 1930s, when hundreds of thousands of people were killed by the firing squads of the NKVD secret police, often on absurd, trumped-up charges.

After a spurt of openness after perestroika reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the archives of the KGB and its forerunners have become less accessible.

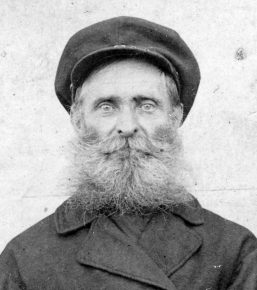

Stepan Karagodin died during Stalin’s purges but the details were hushed up

Last year President Putin, a former KGB lieutenant-colonel and later head of its successor, the FSB, commissioned a monument in Moscow to commemorate victims of political repression.

Yet many politicians prefer to gloss over the purges in favour of praise for Stalin’s leadership in the Second World War.

While Nazi perpetrators of terror were prosecuted at Nuremberg, and South Africa confronted its past with a truth and reconciliation commission, Russia has never fully processed its own bloody history. Mr Karagodin’s search, however, has captured the public’s imagination and given a glimpse of how a reckoning might work.

Stepan Karagodin was a farmer who was arrested in 1937 for allegedly being the leader of a Japanese spy cell. His wife and their nine children knew nothing of his fate until 1955, when she was told that he had died in a prison camp.

Only decades later, as the Soviet Union crumbled, did the family discover that he had been shot.

In 2012 his great-grandson resolved to find out who had killed him: “I started going to the FSB office, sitting at a scratched old table and copying notes from my great-grandfather’s file while an archivist looked over my shoulder.”

After years of cross-referencing documents with tips from other victims’ descendants, he was able this month to obtain the execution order from an FSB archive in the city of Novosibirsk. It revealed that three people — an assistant to the head of the city’s prison called Nikolai Zyryanov, the head of the city’s NKVD department and a secret police inspector — had signed to confirm that Stepan Karagodin and 35 others were shot in Tomsk on January 21, 1938. Denis Karagodin was in shock when the FSB handed over the document. “I think they hardly knew themselves what they were doing.”

Something extraordinary followed. This week he received a letter from Zyryanov’s granddaughter, Yuliya, who had read the news on his blog.

“I haven’t been able to sleep for several days,” she wrote. “My mind tells me I am not to blame for what happened but I cannot describe the feelings I am experiencing.”

Yuliya had not known of her grandfather’s past. One of her own great-grandfathers had been arrested and never seen again, “so it turns out there were victims and executioners all in one family”, she wrote. “The grief that such people caused can never be atoned for. The task of the next generations is to not hush up these events. I thank you and ask forgiveness.”

Mr Karagodin wrote back. “I wanted her to know that we didn’t blame her for anything. I told her to live on with a tranquil soul and a clean conscience.”

Vasily Khanevich, the director of a museum about NKVD brutality in Tomsk, said the case brought hope. “These repressions were committed against our citizens by our citizens — they caused a rupture in society. We need to heal this, and things like [this] project lead to reconciliation.”

Последнее обновление: Среда, 6 февраля, 2019 в 05:27.

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА