Старейшее издание Северной Америки и мира – деловая газета "The Wall Street Journal" (город Нью-Йорк) опубликовала статью о нашем РАССЛЕДОВАНИИ:

A Russian Fights for Stalin’s Victims. – Friday, 16 December 2016, 14:00 GMT, The Wall Street Journal.

Специальный репортаж из Томска (на основе многочасовой беседы с Денисом Карагодиным и городской экспедиции по местам событий) нарратора James Marson:

A Russian Fights for Stalin’s Victims. Nearly 80 years ago, Joseph Stalin’s secret police shot the great-grandfather of Denis Karagodin. Now he has shaken Russia with a landmark investigation. <...>"They buried him here and thought the story was over," says Mr. Karagodin, a fast-talking 34-year-old who shares the intense eyes that stare out from photographs of his great-grandfather. Stepan was a victim of the Soviet dictator's Great Terror against so-called enemies of the people. He had been charged with spying for Japan, but in 1955, after Stalin's death, Stepan's name was cleared. "With that, they thought that the matter was settled," said Mr. Karagodin. "I wanted to show that it wasn't."<...> – Friday, 16 December 2016, 14:00 GMT, The Wall Street Journal – http://www.wsj.com/articles/a-russian-fights-for-stalins-victims-1481896844

Благодарим автора James Marson и газету "The Wall Street Journal" за проявленный интерес, профессионализм и объективную подачу информации.

Спасибо!

A Russian Fights for Stalin’s Victims

Nearly 80 years ago, Joseph Stalin’s secret police shot the great-grandfather of Denis Karagodin. Now he has shaken Russia with a landmark investigation

By JAMES MARSON

Dec. 16, 2016 9:00 a.m. ET

Denis Karagodin holds up a copy of the order to execute his great-grandfather near the ravine in Tomsk, Russia, where the body is buried.

Denis Karagodin is unearthing some uncomfortable truths buried for decades in a trash-strewn ravine on the outskirts of the Siberian town of Tomsk.

Nearly 80 years ago, Joseph Stalin’s secret police shot his great-grandfather Stepan and dumped the body here. Now Mr. Karagodin has shaken Russia with a landmark investigation that he says has unmasked all those involved in the killing.

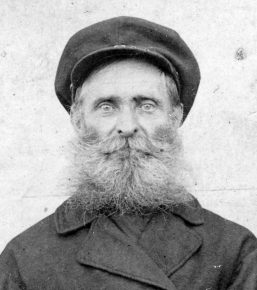

“They buried him here and thought the story was over,” says Mr. Karagodin, a fast- talking 34-year-old who shares the intense eyes that stare out from photographs of his great-grandfather. Stepan was a victim of the Soviet dictator’s Great Terror against so- called enemies of the people. He had been charged with spying for Japan, but in 1955, after Stalin’s death, Stepan’s name was cleared. “With that, they thought that the matter was settled,” said Mr. Karagodin. “I wanted to show that it wasn’t.”

He spent five years tracking down documents in the archives of the security service and other state agencies. His research allowed him to piece together a chain of orders that incriminate, he says, some 30 people, from Stalin right down to the three alleged executioners.

The investigation broke new ground in Russia, where the state—led for 17 years by the ex-KGB colonel Vladimir Putin—largely glosses over the crimes of the Stalin era. The Kremlin venerates the Soviet Union’s victory in World War II and the industrialization that took place under Stalin; it largely ignores the many millions who were killed or exiled for ideological reasons during his reign.

The Russian public has moved closer to the Kremlin’s approach. An August 2007 poll by the independent research organization Levada-Center found that just 9% of Russians saw Stalin’s repressions as a political necessity that was historically justified; a poll this past March found that 26% now share this view. Nine years ago, 72% called the repressions a political crime; in this year’s poll, only 45% did.

For years, individuals have been able to gain access to the case files of persecuted family members. But historians say that Mr. Karagodin’s efforts, chronicled on his blog, are unusual in their diligence and detail—and in his determination to expose the perpetrators. Days after Mr. Karagodin completed his investigation, the history and human-rights group Memorial published an online database of around 40,000 officials of the NKVD (the Soviet secret police) who served during the late 1930s.

The two events sparked debates in newspapers, online and on political talk shows. Should Russians look for the perpetrators of decades-old crimes? Would it lead to reconciliation or a new split in society?

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov declined to comment on Memorial’s database. “The issue is very sensitive,” he told reporters in late November. “It’s clear that opinions differ; there are diametrically opposed views. Both sides make good arguments.”

Mr. Karagodin’s family knew nothing of Stepan’s fate until 1955, when an investigator came to ask questions as authorities revisited the case; he told them, incorrectly, that Stepan had died while in prison.

In spring 2012, Mr. Karagodin found an old notebook where his father had scribbled down information about the case. Days later, he walked into the Tomsk office of the FSB (the successor of the NKVD and KGB) and told the officer on duty, “There’s been a murder.”

‘I asked logical and simple questions that they aren’t used to hearing.’

He was allowed to see the case files, but he soon realized that there were huge gaps. He turned to the FSB official seated next to him: “Where’s the body? Have the people who killed him been brought to account?” he recalled asking. “They were shocked,” he says. “I asked logical and simple questions that they aren’t used to hearing.”

Denis sent requests to archives across the country. The more obstacles officials threw in his way—“There is no information” was a typical response—the more his resolve stiffened to uncover everyone involved.

Each document led to another order, another list, another photograph, slowly revealing a chain that started with Stalin himself. The Soviet dictator signed a decree in 1937 calling for the arrest and execution of “anti-Soviet elements.” Orders from his NKVD chief, Nikolai Yezhov, followed, including one listing the numbers to be shot or sent to the Gulag in each region.

Stepan Karagodin, born in 1881 in a village 200 miles south of Moscow, was an obvious target. He had been exiled to a village north of Tomsk, in central Russia, in 1928 during a campaign against kulaks, or wealthy peasants. The NKVD arrested him on Dec. 1, 1937; he confessed to being a Japanese spy two days later and was executed on Jan. 21, 1938. Documents uncovered by Denis indicate that the confession was false and had been obtained by torture; Stepan was later cleared.

Stepan Karagodin, in a family photograph dated 1930

Cases such as Stepan Karagodin’s were nothing unusual: More than one

million people were executed for political crimes under Stalin, while millions more were sent to the Gulag or were deported, according to Nikita Petrov, a historian at Memorial.

Piece by piece, Mr. Karagodin built his case, tracing prosecutors, security agents and even drivers of the black cars that transported the arrested. On Nov. 12, he received the final link in the chain: a copy of the execution order and a signed note from three executioners confirming to superiors that it had been carried out. “We got them all!” he declared on his blog.

Critics of Mr. Karagodin and Memorial say that pointing fingers over the past revives old enmities and creates fissures in society. In a debate on state television last month, the

chief editor of Komsomolskaya Pravda, a leading pro-Kremlin tabloid, said that people should concentrate on problems in the present. “Let’s not dig into it. They’re all dead,” said the editor, Vladimir Sungorkin.

But Mr. Karagodin’s supporters say that Russia needs to talk about its past to allow reconciliation and prevent a repeat of this grim history. “Nothing splits society more than silence on the topics of suffering and repression of our own people,” said Mr. Petrov from Memorial. “We need understanding of good and evil and not an illusion that all is well in society.”

A week after completing his investigation, Mr. Karagodin received an email from the granddaughter of one of the executioners; she had found out about her grandfather’s role from the blog. “I haven’t slept for several nights,” wrote the granddaughter, whom Mr. Karagodin named only as Yulia. “Mentally, I understand that I’m not responsible for what happened, but I can’t put my feelings into words.”

One of her own great-grandfathers had been arrested and was never seen again. “So now it turns out that there are victims and executioners in one family,” she wrote.

Mr. Karagodin wrote back offering reconciliation: “You won’t find in me an enemy or an assailant, just a person who wants to put an end once and for all to this endless Russian bloodbath.”

James Marson

Последнее обновление: Воскресенье, 27 января, 2019 в 06:57.

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА