Ведущая североамериканская газета "The Washington Post" вышла с большой статьей о "Расследовании КАРАГОДИНА".

Текст вышел как на сайте издания, так и в его бумажной версии!

Автор – Robyn DIXON, лично посетила город Томск (в начале апреля) и взяла почти трех-часовое интервью у Дениса КАРАГОДИНА – руководителя следственной группы "Расследование КАРАГОДИНА".

Пара прямых цитат:

"He spent years uncovering the Stalin-era execution of his great grandfather. Lawsuits seek to bury the evidence." – [May 9, 2021 at 5:00 p.m. GMT+7] by Robyn DIXON () – The Washington Post.

"<...> Karagodin, who is working on a doctoral thesis when not researching, is facing two legal cases seeking to shut down karagodin.org, a sprawling online museum recounting his discoveries, full of documents, fascinating historical tangents — and a tab with the heading “murderers.”<...>"

"If Karagodin is sanctioned by the courts, it would mark another ominous turn as Russian security chiefs tighten their grip and Putin cracks down on activists, journalists and opponents such as jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny.

Karagodin’s efforts for justice and transparency also offer a template for others to follow — provided they have the energy and time to overcome bureaucratic resistance. <...>"

“There’s been a murder,” he told the FSB major, asking to see the archive. The major, surprised, countered: “Write a request. <...>"

"Karagodin is planning a podcast to drum up public pressure."

He spent years uncovering the Stalin-era execution of his great-grandfather. Lawsuits seek to bury the evidence. https://t.co/92YssGBU3I

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) May 10, 2021

В статье (помимо прочего) затронуты темы:

- Сын (МИТЮШОВ Сергей Алексеевич) сотрудника НКВД (МИТЮШОВА Алексея Алексеевича), принимавшего участие в массовых убийствах советских граждан в 1937-1938 годах (на территории города Томска и Новосибирской области СССР), написал донос на Дениса КАРАГОДИНА – руководителя следственной группы "Расследованию КАРАГОДИНА" (KARAGODIN.ORG).

Сын сотрудника Новосибирского НКВД подал заявление в полицию на руководителя следственной группы "Расследование КАРАГОДИНА" Дениса КАРАГОДИНА, обвиняя его в якобы дискредитации имени своего отца.

- Человек признанный Екатеринбургским гарнизонным военным судом лицом "своими действиями причинившим материальный ущерб государству в лице военного училища" – ПРОКОФЬЕВ Мечислав Денисович написал донос на Дениса КАРАГОДИНА – руководителя следственной группы "Расследованию КАРАГОДИНА" (KARAGODIN.ORG).

МВД России провело проверку Дениса КАРАГОДИНА – руководителя следственной группы "Расследование КАРАГОДИНА" и (отдельно) сайта KARAGODIN.ORG, – и приняло решение о передаче материалов в Следственный Комитет России! Денису инкриминируют уголовные и административные статьи.

He spent years uncovering the Stalin-era execution of his great grandfather. Lawsuits seek to bury the evidence.

By Robyn Dixon

Moscow bureau chief – The Washington Post

May 9, 2021 at 5:00 p.m. GMT+7

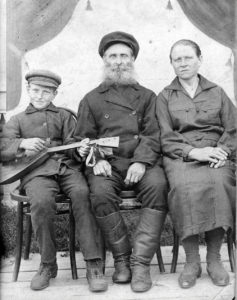

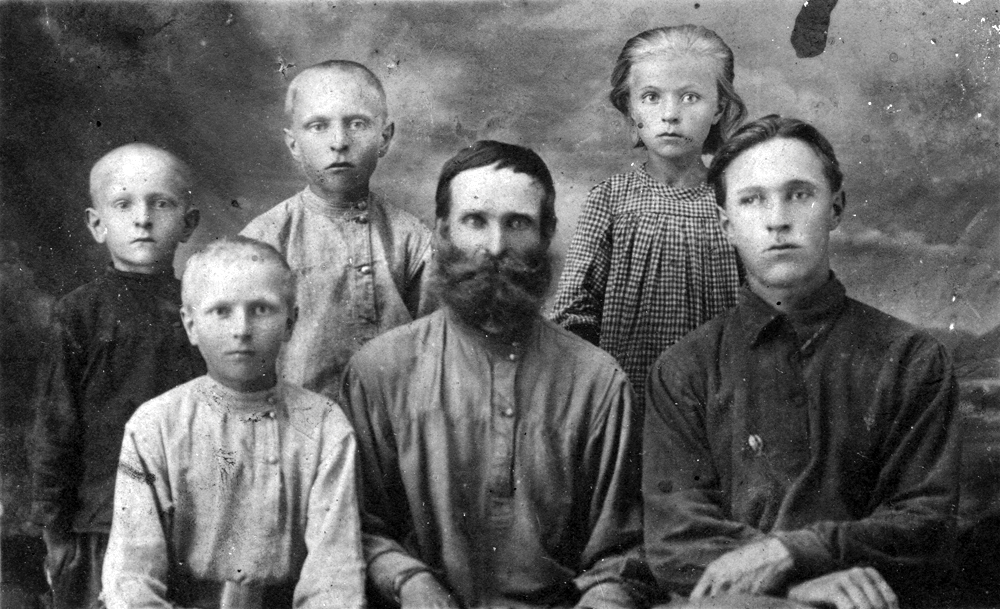

Stepan Karagodin, center, was a prosperous peasant farmer and village leader who resisted the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution. His great-grandson Denis Karagodin has spent years piecing together Stepan’s life and details of his execution in 1938. In this photo, Stepan is shown in exile with his wife, Anna, and youngest son, Lev.

TOMSK, Russia — As cold cases go, Denis Karagodin's mission was as bleak as the winter in his native Siberia. For nine years, he has been digging into Russian and Soviet archives to find out who killed his great-grandfather Stepan Karagodin in 1938 during the purges and iron-fist rule of Joseph Stalin.

The Karagodin family had long believed that Stepan, a peasant farmer, died of tuberculosis in a Soviet prison camp in 1943, serving time for anti-Soviet activities. Karagodin uncovered the real story bit by bit: Stepan was shot by Stalin’s secret police five years earlier on the false charge that he was spying for Japan. He was posthumously exonerated in the 1950s.

But digging up the truth from the past can still bring trouble in today’s Russia.

Karagodin, who is working on a doctoral thesis when not researching, is facing two legal cases seeking to shut down karagodin.org, a sprawling online museum recounting his discoveries, full of documents, fascinating historical tangents — and a tab with the heading “murderers.”

At the same time, access to sensitive archives — opened in the 1990s by President Boris Yeltsin — had grown more difficult under President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer.

In 2014, authorities extended the classification of secrets in the archives of the KGB and the NKVD, another Soviet secret police agency, until 2044, saying that their release would “jeopardize Russian security.”

Under Putin, official propaganda has sought to glorify Russia as a victim of foreign aggression that saved the world in World War II, meanwhile playing down the horrors of Soviet massacres and repressions including the “Great Terror” that Stalin led in the 1930s.

“Fasten your seat belts, dear friends. A case has been filed against me with the police,” Karagodin posted on Facebook on March 3. Sergei Mityushov, the son of a member of Stalin’s secret police, filed the case saying karagodin.org discredited his father, who died in 1967. Within weeks, another case popped up.

If Karagodin is sanctioned by the courts, it would mark another ominous turn as Russian security chiefs tighten their grip and Putin cracks down on activists, journalists and opponents such as jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny.

Karagodin’s efforts for justice and transparency also offer a template for others to follow — provided they have the energy and time to overcome bureaucratic resistance.

'A classic peasant'

Karagodin said his family, beginning with Stepan’s illiterate wife, Anna, has been seeking the truth over generations.

Russia’s FSB, successor to the KGB and the NKVD, “tried to block me from getting the documents,” Karagodin said. But he added: “We got nearly all of [them].”

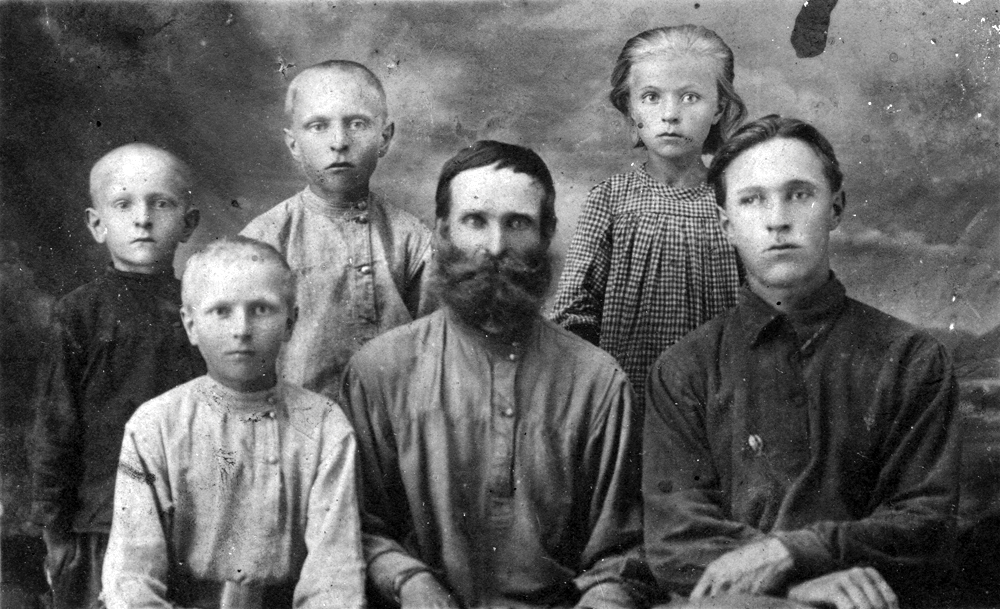

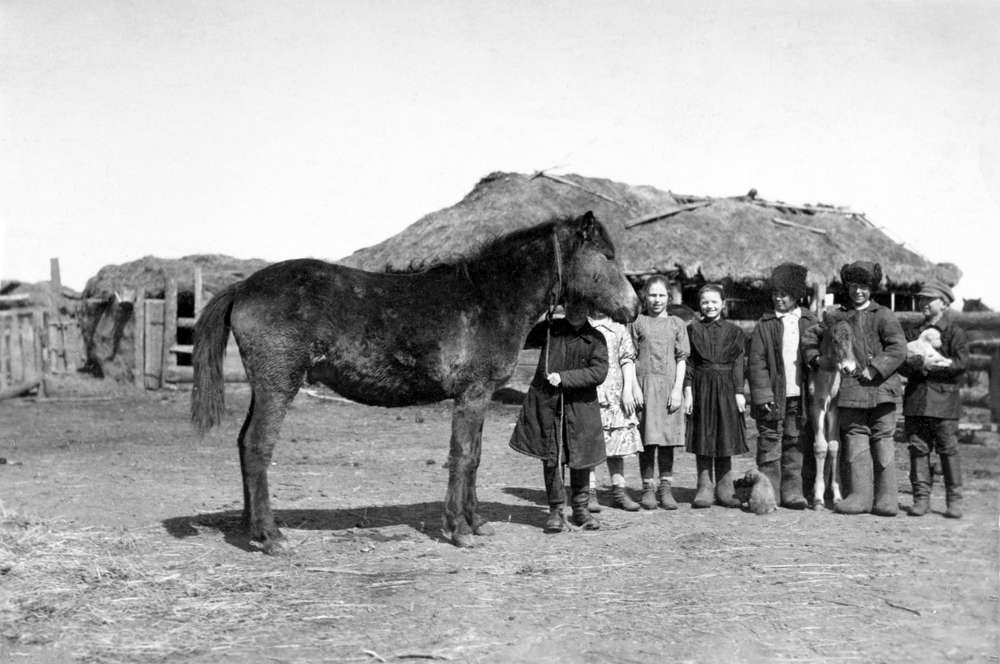

Stepan Karagodin, center, is pictured with his children when he was a farmer in the Volkovo village in the Russian Far East in the early 20th century.

Karagodin’s research, piece by piece, built a portrait of Stepan as a stubborn man who cherished his freedom, hated the Bolsheviks who took away his rights and wasn’t afraid to speak his mind.

“He was a classic peasant who wanted to have his own property and did whatever he could to achieve it,” his great-grandson said.

Karagodin’s quest began in 2012 when he was clearing out a family cupboard. He found Stepan’s posthumous exoneration notice from the 1950s, which offered little detail.

Curious, he filed a request for the death certificate and found that Stepan did not die in prison, but was executed in 1938 by “shooting.” Karagodin went to the local FSB headquarters in Tomsk, a city in Siberia about 1,600 miles east of Moscow.

“There’s been a murder,” he told the FSB major, asking to see the archive. The major, surprised, countered: “Write a request.”

Later, Karagodin was given just two hours in the archive under watch. He discovered that his grandfather had been accused of setting up a web of six alleged Japanese spies who Soviet authorities said had planned to blow up factories and other sites. All were executed in January 1938.

“These people were [later] recognized as innocent. Where is the list of those who killed them?” he asked the FSB officer, who told him to write another request.

And so it went, throughout his quest. Karagodin would pull one thread, then another and another.

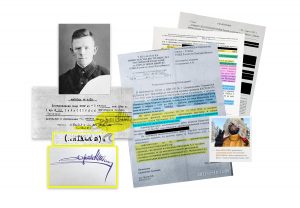

He sent off innumerable requests to the archives of the FSB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the prison service, the military and regional prosecutors, regional and municipal archives, and other agencies across a vast slice of Russia, transcribing and uploading hundreds of historical documents.

He crowdsourced funding and help. The “murderers” tab on his website grew longer.

Stepan Karagodin’s farm and some of his 11 children and relatives are pictured in the Russian Far East. Karagodin despised the Bolsheviks, scorning the slogan “proletariats of the world unite,” because it meant that peasant farmers would be stripped of their hard-won farmland and possessions.

Journey across Russia

Stepan Karagodin was born 1881 to poor landless peasants in western Russia’s Oryol region. He moved to a Cossack village in Kuban, southwest of Moscow, and married a Cossack girl, Anna, but was denied land.

In the early years of the 20th century, he made a three-year journey across Russia with his family, other relatives and most of his village in search of land in the Far East.

Stepan was given land and became village chief and a kulak, or rich peasant farmer. He had 11 children. By the 1917 Russian Revolution, he and his brother Fyodor had 200 acres [Correction: 538,46 acres (Stepan's only, excluding his brother. Source: "В результате к 17 году они обрабатывали до 200 десятин земли.") – KARAGODIN.ORG] and extensive farm machinery.

He “had a great craving for culture” and loved to read the newspaper or chat with educated people, his nephew Ivan Mikhailov wrote. Stepan scorned the Bolshevik slogan “Proletarians of the world unite.”

“They say the hicks, smugglers, tramps are united, but the end is coming to us, the owners. Boss power, not our peasant power,” Mikhailov reported him saying.

The Karagodins fought against the Bolsheviks with the White Russian army and their Japanese allies. Bolsheviks passed through their village in 1920, stole Stepan’s horse and cart and a fur coat and killed his nephew Georgy, leaving Stepan raging in “wild hatred for everything that existed,” Mikhailov wrote.

He was jailed for three months in 1921, accused of forming an anti-Soviet group, but was freed for a bribe. In 1928, his village booed Bolshevik officials taking their land for new settlers. He called communist education “useless” and rebuffed officials with tax demands.

He was arrested, stripped of all his belongings and exiled for three years to a remote Siberian settlement.

Denis Karagodin is pictured in 2016 in Tomsk, Russia, at the site where he thinks his great-grandfather’s body was dumped, holding the act of execution. Historians found two skulls with bullet holes at the site in the late 1980s, but local authorities have never investigated.

“Life here will be no more. They won’t allow it,” Stepan wrote in a note to his family. “Everyone, scatter urgently, wherever you can.”

After exile, he and his family started anew in Tomsk. He was arrested on fabricated spying charges in December 1937 and shot seven weeks later.

“It was not personal,” Karagodin said of the killers. “It was bureaucratic work.” Moscow sent orders to purge kulaks and anti-Soviet elements, and local officials fulfilled, or sometimes exceeded, the order.

During his quest for answers, Karagodin traveled to Russia’s Far East and stood on the open stretch his grandfather once farmed, feeling a visceral tug into the past.

“When you know how many people were killed, just because they lived and did their jobs, when you know they were tortured and killed for trying to survive, you realize you have to do something about it,” he said.

Sentence 'fulfilled'

In 2016, Karagodin got hold of the official act on Stepan’s execution and six others dated Jan. 31, 1938, bearing three signatures: Sergei Denisov, a local NKVD boss; Nikolai Zyryanov, commandant of Tomsk Prison No. 3; and Yekatarina Noskova, an NKVD inspector. The paper noted the sentence was “fulfilled.”

Alexei Mityushov, an NKVD inspector in Novosibirsk who died in 1967, is listed on karagodin.org because he signed an extract stating that the execution took place.

Mityushov’s son Sergei declined to be interviewed about why he took legal action to shut down the website, but told Russian media that it “crossed a political line.” He said the NKVD’s job was to “fight criminals and their relatives,” working in “a hard, harsh time.”

To him, the NKVD, the KGB and the FSB were always “the elite. They set an example to others.”

A separate complaint was filed to police against Karagodin for allegedly violating the privacy of NKVD employees and libel. He did not respond to requests for an interview.

Karagodin believes Stepan’s body was dumped in Tomsk’s Kashtak neighborhood, a suspected execution site where bones, buttons and clothing fragments turned up in the soil. Local authorities have refused to investigate.

He wants to recover Stepan’s bones for a family burial, but his request to the regional FSB to return the body was denied in 2016. Karagodin is planning a podcast to drum up public pressure.

His final, but unlikely, goal: a posthumous murder trial.

“Bringing the case to court would be a way to get revenge,” he said, “to deal with your feelings.”

Original Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/russia-stalin-history-family-execution/2021/05/07/0c296b28-8c0e-11eb-a33e-da28941cb9ac_story.html

Последнее обновление: Четверг, 20 мая, 2021 в 17:48

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА