In English

По-русски (полная версия)

По-русски (сокращённая версия)

W języku Polskim (krótka)

W języku Polskim (więcej)

Аuf Deutsch (kurzfassung)

Аuf Deutsch (vollversion)

A murder puzzle has consumed this man's family for generations.

One man has spent four years trying t find out what happened to his great-grandfather who was executed by Stalin.

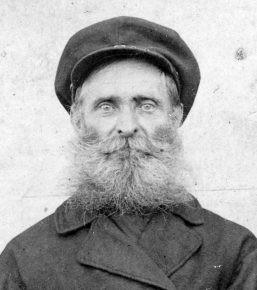

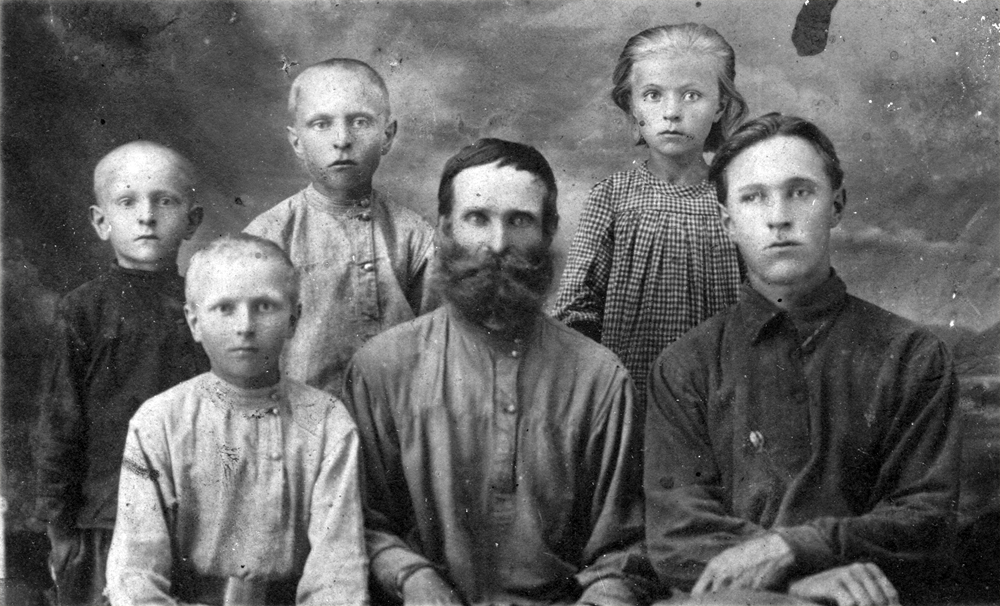

Stepan Ivanovich Karagodin (center) was executed in 1938 after being deemed a Japanese spy amid dictator Josef Stalin's Great Terror.

Denis Karagodin had something important to say when he walked into the regional branch of Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) – the main successor agency to the Soviet KGB – in the Siberian city of Tomsk.

"There's been a murder," Karagodin, now a 33-year-old designer, told the major manning the front desk.

The officer was perplexed at first: "Excuse me?" Karagodin recalls his interlocutor saying.

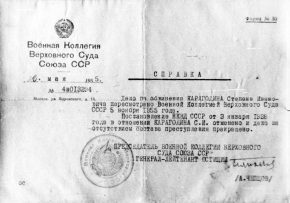

To explain himself, the visitor produced a copy of a certificate. The officially stamped document, dated 1955, confirmed the Soviet authorities had rehabilitated his great-grandfather, Stepan Ivanovich Karagodin, who was executed in 1938 after being deemed a Japanese spy amid dictator Josef Stalin's Great Terror.

The officially stamped document, dated 1955, confirmed the Soviet authorities had rehabilitated Stepan Ivanovich Karagodin

"He said: 'I see. Send an official request,'" Karagodin tells RFE/RL's Russian Service.

It was the beginning of what has become a mission for Karagodin, a philosopher by education who has immersed himself in a murder puzzle that has consumed his family for generations: How and why Stepan Ivanovich was killed, who executed him, and where his remains were discarded.

"I want to know the names of all the people who participated in the execution, and I will get them," Karagodin says. "Sooner or later, it will happen."

The result has been an exhaustively chronicled account of the fate of Stepan Ivanovich, a Cossack grain farmer and father of nine, complete with documents from Russian secret-service archives that Karagodin has published on a website dedicated to the family patriarch.

For Karagodin, the quest to document the precise circumstances of his great-grandfather's death is deeply personal: In the years following his execution, Stepan Ivanovich's wife and family had no idea whether he was dead or alive. "The search to establish his fate has never stopped: Each generation of our family has done all it can," he says.

But his research has drawn praise from prominent voices in Russian for its broader implications, chiefly the public reckoning with the crimes of Stalin, whose Great Terror is estimated to have killed more than 1 million people.

It also comes amid a softening public view in Russia of Stalin and his violent repressions -- a trend that Russian President Vladimir Putin's critics accuse the Kremlin of fostering and exploiting for political gain.

Andrei Zubov, a professor of philosophy and noted political commentator, called the project a "very important and necessary" endeavor.

"The descendants of the murdered should know the murderers, and the descendants of murderers should know the descendants of the murdered -- and that their ancestors were murderers," Zubov wrote on Facebook recently. "Silence will not make a national reconciliation is possible; only the comprehensive knowledge of the past will," he added.

'A Matter Of Time'

Karagodin has investigated his great-grandfather's murder with the persistence and meticulousness of a police detective piecing together enough evidence for a successful prosecution. His website serves as a kind of digital corkboard bearing photographs, bios, and documents about officials with Stalin's notorious enforcers, the NKVD, implicated in the killing.

So far he has collected information about some two-dozen suspects, tracing the chain of responsibility from Stalin to his bloodthirsty NKVD chief, Nikolai Yezhov, and down the line all the way to local secret-service officials in Tomsk.

"The only people who haven't been established are those who directly participated in the executions" of Stepan Ivanovich and several other accused conspirators, Karagodin says.

"But the basic list of names has already been drawn up," he says. "I know, for example, that as a basic courtesy the investigator himself would be among those involved. Establishing this is just a matter of time."

Historians and researchers say that access to KGB archives has become increasingly restricted since Putin, himself a former KGB officer, rose to power 16 years ago. In December, the government's commission on state secrets rejected transparency activists' petition to open up the archives of Soviet security services, saying that doing so "could harm the security of the Russian Federation."

While Karagodin has been able to access his great-grandfather's files in archives maintained by the FSB, he says he has been unable to gather materials about those who organized and carried out the killing directly from these collections. "The state security services are doing everything they can to make this impossible," he says.

The FSB has been equally taciturn about the location of Stepan Ivanovich's remains, Karagodin says. He believes his great-grandfather's body was dumped in a notorious Kashtak ravine in Tomsk, where experts believe some 15,000 or more victims of Stalin's repression may have been dumped in a mass grave (+).

Karagodin says he submitted a request with the regional FSB branch asking for his great-grandfather's body but that the agency said the relevant documents were in poor condition -- a justification he calls a feeble excuse.

"I know with 100 percent certainty that they know exactly where the executions were carried out. The entire city knows it," he says.

'Did This Century Even Happen?'

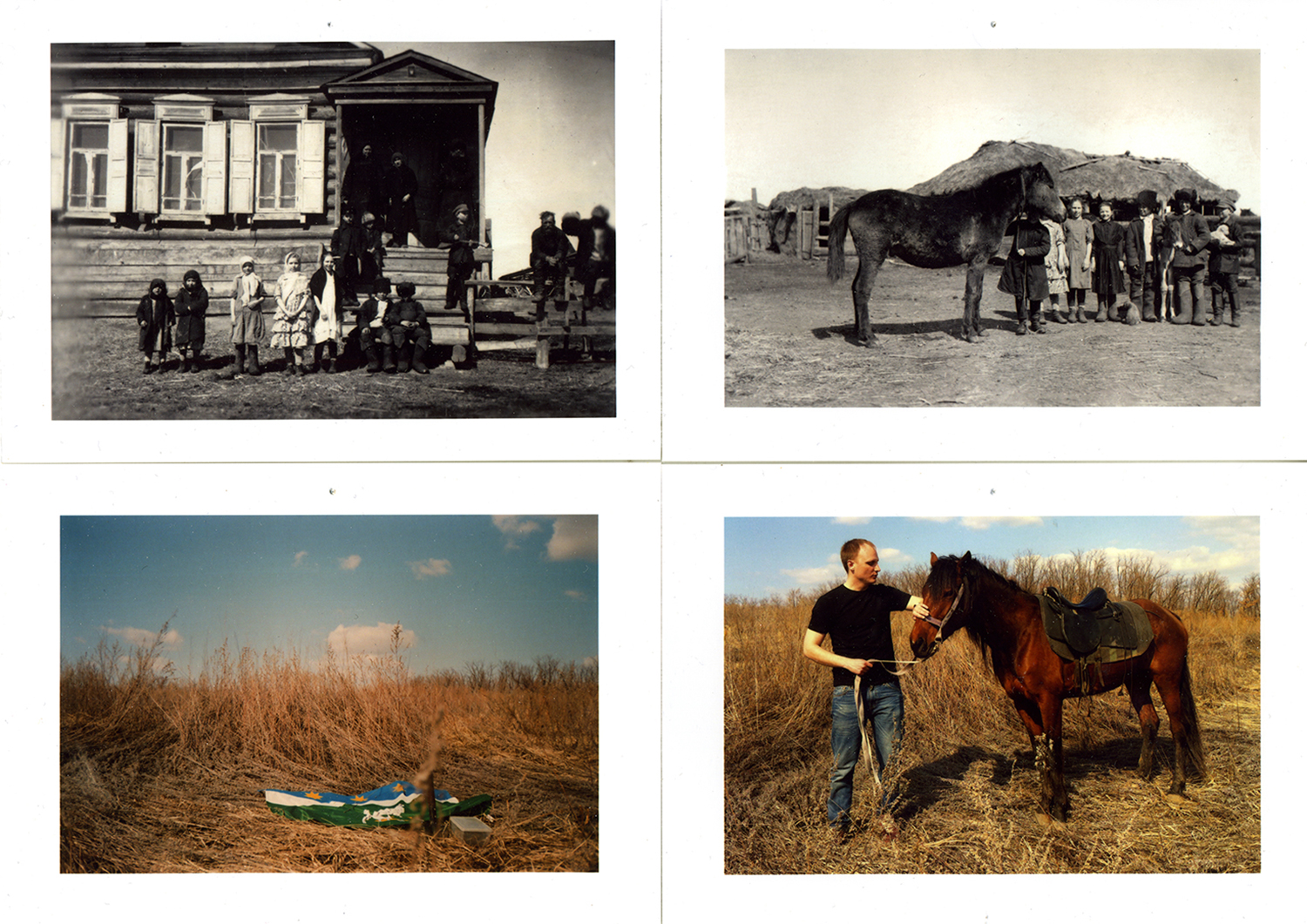

Born in 1881 in the Oryol Governorate on the Russian Empire's western flank, Stepan Ivanovich Karagodin and his family moved across the continent to the village of Volkov outside the Far Eastern city of Blagoveshchensk in the early 20th century.

He became a successful farmer and community leader who ultimately supported the provisional government against the Bolsheviks after the fall of Tsar Nicholas II, for which he was later arrested and jailed for three months.

In 1928, he was again arrested and convicted of "counterrevolutionary sabotage" and exiled to Siberia for three years, after which he made his way to Tomsk. It was there that he was arrested in December 1937, accused of organizing a group of "diversionists" and spies for Japan – charges for which he was ultimately executed. He was later rehabilitated of the allegations in both cases.

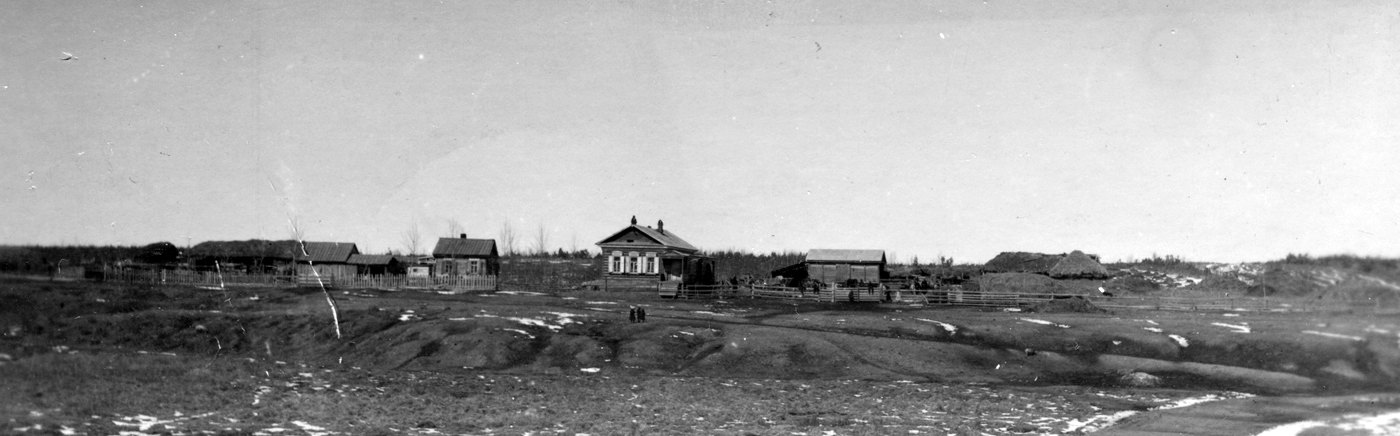

About a year into his research, Karagodin traveled to the village of Volkovo outside Blagoveshchensk carrying a withered photograph of Stepan Ivanovich's family home on 200 hectares or so of farmland. Having established GPS coordinates of the property, he visited the location where the farm once stood. Locals told him that the home was torn down in the 1960s or 1970s.

The propetry of Stepan Ivanovich Karagodin in Voloko.

Standing where his great-grandfather did at the beginning of the 20th century was almost a "religious experience," Karagodin says.

"I saw exactly what Stepan Ivanovich saw a little more than 100 years ago, in 1901-02," he says. "Just like him, I saw a barren place. What's more, we were about the same age. And I thought to myself: Did this century even happen?"

Written by Carl Schreck based on reporting by Dmitry Volchek of RFE/RL's Russian Service

Original:

One Russian's Search For His Great-Grandfather's Soviet Police Killers – by Carl Schreck and Dmitry Volchek – Jun 23, 2016 – © Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, RFE/RL.

Последнее обновление: Вторник, 27 сентября, 2016 в 15:01.

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА